What manuscripts have survived to modern times, and how did their incomplete contents create different versions of the Nights we have today?

Since no ancient manuscript contains all the stories, how can a collector assemble a “complete” collection and find “orphan tales” like Aladdin and Ali Baba without original sources?

How do we determine which stories are “authentic” to the medieval Arabic tradition versus later additions, and what is the definitive list of all known tales?

The Origins

The Thousand and One Nights is not a book in the conventional sense but rather a textual tradition, a vast and evolving repository of stories transmitted orally and in manuscript form across numerous cultures and centuries. Understanding its origins requires dismantling the myth of a singular source and embracing the reality of its composite and anonymous nature.

The Myth of the Single Author and the Reality of Composite Origins

- There was no single author of The Thousand and One Nights.

- The work is the product of countless anonymous storytellers, scribes, and redactors working over a period of nearly a millennium.

- This anonymity and its classification as popular, rather than high, literature meant that it was largely ignored by classical Arabic literary critics.

- Ibn al-Nadim, a 10th-century Baghdadi bookseller, famously dismissed an early version of the work as being of little literary value.

- This very lack of a fixed, canonical form, however, was the key to its extraordinary adaptability and enduring appeal, allowing it to absorb new material as it traveled from culture to culture.

The earliest identifiable core of the collection is not Arabic but Persian. Tenth-century Arab historians like al-Mas’udi and Ibn al-Nadim refer to a Persian work titled Hezār Afsān (هزار افسان), meaning “A Thousand Tales”. This collection, likely of Indo-Persian origin, was translated into Arabic around the 8th or 9th century and is believed to have provided two foundational elements that define the Nights to this day: the frame story of the clever vizier’s daughter, Shahrazad (Scheherazade), who tells stories to the murderous King Shahryar to save her life, and the central organizing concept of a collection spanning a “thousand” nights.

Following its introduction into the Arabic-speaking world, this core collection underwent a profound transformation. Over the subsequent centuries, particularly during the Islamic Golden Age in Baghdad, the tales were “Arabicized”. Scribes and storytellers integrated new narratives that reflected the sophisticated urban life of the Abbasid Caliphate, including a cycle of tales featuring the Caliph Harun al-Rashid (ruled 786-809 CE) and members of his court.

Later, as the center of gravity of the Arab world shifted, a distinct layer of stories with a Cairene provenance was added, reflecting the culture and dialect of Mamluk Egypt. This process of accretion resulted in a multi-layered text with strata from India, Persia, Iraq, and Egypt, all unified within the overarching Arabic frame.

The earliest physical evidence

While historical accounts point to an early existence, the physical evidence for the Nights is sparse until the late medieval period. The two most significant artifacts for understanding the early text are a 9th-century paper fragment and a 14th/15th-century manuscript.

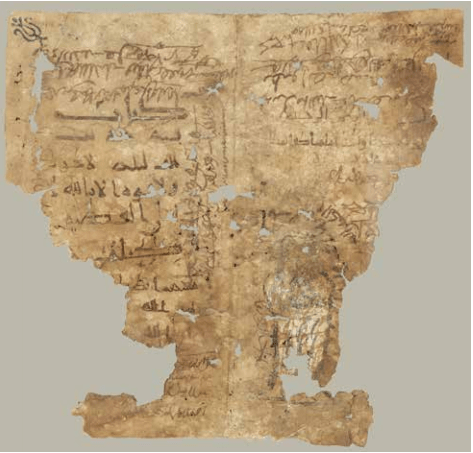

The 9th-Century Abbott Fragment

The oldest known physical evidence of the Nights is a single sheet of paper discovered in Syria and acquired by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago in 1947. Analyzed and identified by scholar Nabia Abbott in 1948, the fragment has been dated to the early 9th century CE. It is a remarkable document, containing on its front side the title, written as Kitab Hadith Alf Layla (“The Book of the Tale of the Thousand Nights”), and the opening lines of the frame story, in which Dinazad asks Shahrazad to begin her storytelling. The reverse side and margins of the paper were used as scrap for pious phrases, drafts of letters, and legal formulas, one of which is dated to the year 879 CE. The fragment’s use as scratch paper confirms that the work was in circulation at this early date, but also reinforces the view that it was considered popular entertainment rather than a work of high literary art worthy of careful preservation.

The Galland Manuscript

For centuries, the earliest extensive manuscript of the Nights is a three-volume codex of Syrian origin, dating from the 14th or 15th century. Now housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris (MSS arabes 3609-11), it is commonly known as the Galland Manuscript, after its 18th-century owner, Antoine Galland. This text is the foundational witness for the oldest recoverable branch of the textual tradition, known as the Syrian Recension.

The precise dating of the manuscript has been a subject of significant scholarly debate. Muhsin Mahdi, the manuscript’s modern editor, argued for a 14th-century date based on paleographic and linguistic evidence. However, the German scholar Heinz Grotzfeld later proposed a 15th-century date, based on compelling numismatic evidence, an analysis of the specific types of coins mentioned in the tales, which he argued correspond to coinages that were not in circulation until after 1450.

Regardless of its exact date, the Galland Manuscript is of paramount importance. It is considered by scholars to be the most valuable version from a literary and linguistic standpoint, preserving a purer and more classical style of Arabic than later, more colloquial versions. However, it is crucially incomplete. The text extends for 282 nights, breaking off abruptly in the middle of the “Tale of Qamar al-Zaman and Budur”. It does not contain 1001 nights of stories, nor does it include many of the tales that are now most famously associated with the collection, such as those of Aladdin, Ali Baba, or Sindbad.

This incompleteness reveals a fundamental paradox at the heart of the search for the “original” Nights. The version that is most authentic in terms of its age and scholarly purity, the Syrian recension represented by the Galland Manuscript, is the least complete in terms of popular expectation. Conversely, the versions that are “complete,” containing a full 1001 nights and the famous tales, are products of a much later period and a different textual family that emerged in Egypt. Therefore, the quest for a single “original” is a category error. One must instead choose between two different kinds of authenticity: the authenticity of the earliest recoverable text, which is shorter and more refined, and the authenticity of the most fully developed state of the tradition, which is longer, more varied, and a product of centuries of evolution and, as will be shown, cross-cultural interaction. This distinction is essential for navigating the complex history of the text and understanding the different versions available today.

The Evolution of a Global Classic: Accretion, Invention, and the Making of the Modern Nights

The journey of The Thousand and One Nights from a loose collection of Middle Eastern folktales to a cornerstone of world literature is a story of continuous transformation. The text was never static; it was a living tradition that absorbed new material and adapted to new audiences. This process was dramatically accelerated and fundamentally altered by its encounter with Europe in the 18th century, an encounter that not only introduced the tales to the West but also reshaped the Arabic tradition itself in a complex feedback loop of supply and demand.

The Living Text: Arabic Recensions and the Rise of the Egyptian Tradition

Within the Arabic-speaking world, the Nights existed in multiple forms, transmitted through different manuscript families, or “recensions.” While the Syrian recension, exemplified by the Galland Manuscript, represents the oldest recoverable branch, a younger but far more expansive tradition developed in Egypt.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a new and distinct family of manuscripts began to be produced in Cairo. First systematically identified by the French scholar Hermann Zotenberg in the 1880s, this group is now known as Zotenberg’s Egyptian Recension (ZER). The defining characteristic of the ZER manuscripts is their deliberate effort to compile a collection that contains exactly, or approximately, one thousand and one nights of storytelling. To achieve this, Cairene scribes gathered a vast number of additional tales, love stories, epic adventures, comedies, and fables, that were not present in the older Syrian tradition. These ZER manuscripts became the source texts for the first printed Arabic editions of the Nights, most notably the Bulaq edition (printed in Cairo, 1835) and the Calcutta II edition (printed in India by W.H. Macnaghten, 1839–42). These printed editions, in turn, would form the basis for the great 19th-century “complete” English translations.

The European “Invention” of the Arabian Nights and the Role of Antoine Galland

The global history of the Nights begins with one man: the French scholar and antiquarian Antoine Galland. His twelve-volume translation, Les mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français (1704–1717), was the first European version and a literary sensation. Galland was far more than a mere translator; he was an editor, an adaptor, and, in a very real sense, the creator of the Nights as the West would come to know it.

He based his initial volumes on the three-volume Syrian manuscript that he had acquired in the Levant and brought back to Paris. His translation, rendered in elegant and polished French, transformed the tales. He omitted or softened elements he deemed too coarse or repetitive for his aristocratic audience while enhancing the sense of exoticism and magical wonder. The result was an immediate bestseller that captivated European readers and gave birth to a new literary genre, the “oriental tale”. The demand for more stories was insatiable. When the tales in his manuscript ran out after Night 282, Galland, under pressure from his publisher and the public, began to supplement his work with tales he gathered from other sources. For over a century, Galland’s French text, not any Arabic original, served as the primary source for translations into English, German, and other European languages, cementing his particular version of the collection as the standard.

The “Orphan Tales”: Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sindbad

The most significant and lasting of Galland’s additions were a set of tales that are not found in the Galland Manuscript or any other part of the medieval Arabic manuscript tradition. These are known to scholars as the “orphan tales” because they lack known Arabic manuscript parents predating their appearance in Galland’s French translation.

- Aladdin and Ali Baba: In 1709, Galland met Hanna Diab, a Syrian Maronite Christian from Aleppo who was visiting Paris. Diab was a gifted storyteller, and Galland recorded in his diary a number of tales that Diab recounted to him. Among these were “The Story of Aladdin, or the Magic Lamp” and “The Story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves”. Galland incorporated these stories into the later volumes of his Mille et une nuits. No Arabic manuscript source for these tales has ever been found that predates Galland’s work, leading to the scholarly consensus that they were either original creations of Hanna Diab or part of a separate Syrian oral tradition for which he was the sole literary conduit.

- The Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor: The adventures of Sindbad the Sailor existed as an independent cycle of tales, with its own manuscript tradition, entirely separate from the Nights. Galland encountered a manuscript of the Sindbad stories and, likely believing them to be a part of the larger collection that had become detached, translated and included them in his edition.

The immense popularity of these orphan tales in Europe solidified their place in the canon of the Arabian Nights. From the 18th century onward, any “complete” edition was expected to include them, despite their textually distinct origins.

The history of these additions reveals a fascinating transcultural feedback loop. The European reception of the Nights, initiated by Galland’s hybrid text, created a powerful set of expectations about what the collection should contain. Eighteenth-century European travelers and scholars, armed with Galland’s popular translation, went to the Middle East in search of a “complete” and “original” Arabic manuscript that matched the version they knew. At the time, however, Arabic manuscripts of the Nights were scarce. This intense demand from a wealthy European market created a powerful economic incentive for scribes and booksellers in Cairo to produce new, larger compilations that would satisfy their clients’ expectations. This commercial effort gave rise to the ZER family of manuscripts, the first versions to systematically collect tales to reach the 1001-night total. These newly assembled “complete” manuscripts were then sold to Europeans and became the basis for the 19th-century printed Arabic editions (Bulaq and Calcutta II), which were in turn hailed in Europe as the definitive, authentic source texts. Thus, the modern form of the “complete” Nights is not a purely indigenous creation but a transcultural product, born from a dynamic interplay between an Arab storytelling tradition and a European fantasy of its ideal form.

Timeline of the Evolution of The Thousand and One Nights

- c. 8th-9th Century: The Persian collection Hezār Afsān (“A Thousand Tales”) is translated into Arabic, forming the core of the collection known as Alf Layla (“A Thousand Nights”). Folktales from the oral traditions of Persia, Arabia, and India begin to coalesce.

- c. 9th Century: The earliest physical evidence, the Abbott Fragment, is produced in Syria, bearing the title Kitab Hadith Alf Layla. Tales from the collection reach Baghdad and are expanded with stories reflecting Abbasid court life.

- 10th Century: The Baghdadi bookseller Ibn al-Nadim mentions Hezār Afsān in his Fihrist (Catalogue of Books), attributing to it the frame story of Shahrazad. The historian al-Mas’udi also refers to the collection.

- c. 12th Century: A document from the Cairo Geniza, a synagogue storeroom, refers to a Jewish bookseller lending a copy of The Thousand and One Nights, the first known use of this definitive title.

- 14th-15th Century: The Galland Manuscript, the earliest extensive manuscript of the Syrian recension, is copied. It contains stories for 282 nights.

- 1704–1717: Antoine Galland publishes his seminal French translation, Les mille et une nuits. He translates the Syrian manuscript and adds the “orphan tales” of Sindbad, Aladdin, Ali Baba, and others, creating the hybrid version that would define the Nights in the West.

- 1706: The first anonymous English translation, known as the “Grub Street” version, is published, based on Galland’s French text.

- Late 18th-Early 19th Century: In response to European demand, the Zotenberg’s Egyptian Recension (ZER) manuscripts are produced in Egypt, compiling tales to reach the 1001-night total.

- 1814–1818: The Calcutta I edition, the first printed Arabic version, is published by the British East India Company. It is incomplete.

- 1835: The Bulaq edition, the first complete Arabic text printed in an Arab country, is published in Cairo. It is based on the ZER manuscript tradition.

- 1839–1842: The Calcutta II (Macnaghten) edition, another complete Arabic text based on the ZER tradition, is published in four volumes. This edition becomes the primary source for the most comprehensive English translations.

- 1839–1841: Edward William Lane publishes his influential but heavily expurgated English translation, based primarily on the Bulaq edition and noted for its detailed ethnographic annotations.

- 1882–1884: John Payne publishes the first complete and unexpurgated English translation, The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night, based on the Calcutta II and Bulaq texts.

- 1885–1888: Sir Richard F. Burton publishes his famous 16-volume unexpurgated translation, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, based largely on Payne’s work and the Calcutta II text. It is renowned for its archaic style and extensive, explicit anthropological notes.

- 1984: Scholar Muhsin Mahdi publishes the first critical scholarly edition of the Arabic text, based on the 14th-century Galland Manuscript, restoring the oldest recoverable version of the Syrian recension.

- 1990: Husain Haddawy publishes a highly regarded English translation of Mahdi’s critical Arabic edition, making the Syrian recension widely accessible to English readers.

- 2008: Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons publish a new, complete English translation of the Calcutta II edition for Penguin Classics, providing a modern, scholarly, and accessible alternative to Burton for the full Egyptian recension.

Syrian/Galland Line

- 14th–15th c. → Galland Manuscript (Syrian recension, 282 nights)

- 1704–1717 → Antoine Galland (French) → Les mille et une nuits

- Based on Galland Manuscript

- Adds “orphan tales” (Sindbad, Aladdin, Ali Baba) → hybrid version

- 1706 → Grub Street English → from Galland’s French

- 1984 → Muhsin Mahdi → critical Arabic edition → based on Galland Manuscript (Syrian recension)

- 1990 → Husain Haddawy → English translation of Mahdi → Syrian recension accessible

- 1704–1717 → Antoine Galland (French) → Les mille et une nuits

Egyptian/ZER Line

- Late 18th–Early 19th c. → Zotenberg’s Egyptian Recension (ZER manuscripts) → inflated to 1001 nights

- 1814–1818 → Calcutta I → first printed Arabic (incomplete)

- 1835 → Bulaq edition (Cairo) → first complete Arabic (ZER-based)

- 1839–1841 → Lane (English) → from Bulaq → censored, ethnographic notes

- 1839–1842 → Calcutta II (Macnaghten) → full Arabic (ZER-based)

- 1882–1884 → Payne (English) → complete, unexpurgated → from Calcutta II + Bulaq

- 1885–1888 → Burton (English) → 16 vols, archaic + explicit → built on Payne + Calcutta II

- 2008 → Lyons & Lyons (English) → modern full translation of Calcutta II

- 1882–1884 → Payne (English) → complete, unexpurgated → from Calcutta II + Bulaq

The Complete Canon: A Comprehensive List of the Tales

Defining “Completeness”: A Synoptic View of the Major Recensions

The following table illustrates the core story cycles found in the earliest extensive manuscript (the Syrian recension), the additions present in the later, more comprehensive Egyptian recension, and the famous “orphan tales” introduced into the Western tradition by Antoine Galland. This comparison clarifies which stories constitute the ancient core of the work and which are later additions.

| Story Cycle / Major Tale | Syrian Recension (Galland MS / Mahdi-Haddawy) | Egyptian Recension (Calcutta II / Burton-Lyons) | “Orphan Tales” (Galland’s Additions) |

| Frame Story of Shahryar and Shahrazad | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The Merchant and the Jinni | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The Fisherman and the Jinni | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The Porter and the Three Ladies of Baghdad | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The Tale of the Three Apples | ✔ | ✔ | |

| The Hunchback’s Tale | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Nur al-Din Ali and Anis al-Jalis | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Ghanim ibn Ayyub | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Ali ibn Bakkar and Shams al-Nahar | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Tale of Qamar al-Zaman (incomplete) | ✔ | ✔ | |

| Tale of King Omar ibn al-Nu’man | ✔ | ||

| The Ebony Horse | ✔ | ||

| Abu al-Husn and His Slave-Girl Tawaddud | ✔ | ||

| The City of Brass | ✔ | ||

| Judar and His Brethren | ✔ | ||

| The History of Gharib and His Brother Ajib | ✔ | ||

| Abu Kir the Dyer and Abu Sir the Barber | ✔ | ||

| Ma’aruf the Cobbler | ✔ | ||

| The Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor | (Added to Western editions) | ✔ (Independent Text) | |

| Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp | (Added to Western editions) | ✔ (From Hanna Diab) | |

| Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves | (Added to Western editions) | ✔ (From Hanna Diab) | |

| Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Peri-Banu | (Added to Western editions) | ✔ (From Hanna Diab) |

An Exhaustive List of the Tales of The Thousand and One Nights

The following list details the contents of Sir Richard F. Burton’s complete translation, comprising the ten volumes of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885) and the six subsequent volumes of The Supplemental Nights (1886–1888). This represents the most exhaustive collection of tales associated with the Nights in English, drawing primarily from the Calcutta II edition but also supplementing with tales from the Breslau and other manuscript sources. The hierarchical structure reflects the famous “story-within-a-story” narrative technique.

Volume 1

- Story of King Shahryar and His Brother

- Tale of the Bull and the Ass (Told by the Vizier)

- Tale of the Trader and the Jinn

- The First Shaykh’s Story

- The Second Shaykh’s Story

- The Third Shaykh’s Story

- Tale of the Fisherman and the Jinni

- Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban

- Story of King Sindibad and His Falcon

- Tale of the Husband and the Parrot

- Tale of the Prince and the Ogress

- Tale of the Ensorcelled Prince

- Tale of the Vizier and the Sage Duban

- The Porter and the Three Ladies of Baghdad

- The First Kalandar’s Tale

- The Second Kalandar’s Tale

- Tale of the Envier and the Envied

- The Third Kalandar’s Tale

- The Eldest Lady’s Tale

- Tale of the Portress

- The Tale of the Three Apples

- Tale of Núr al-Dín Alí and his Son

- The Hunchback’s Tale

- The Nazarene Broker’s Story

- The Reeve’s Tale

- Tale of the Jewish Doctor

- Tale of the Tailor

- The Barber’s Tale of Himself

- The Barber’s Tale of his First Brother

- The Barber’s Tale of his Second Brother

- The Barber’s Tale of his Third Brother

- The Barber’s Tale of his Fourth Brother

- The Barber’s Tale of his Fifth Brother

- The Barber’s Tale of his Sixth Brother

- The End of the Tailor’s Tale

- The Barber’s Tale of Himself

Volume 2

- Nur al-Din Ali and the Damsel Anis Al-Jalis

- Tale of Ghanim bin Ayyub, The Distraught, The Thrall o’ Love

- Tale of the First Eunuch, Bukhayt

- Tale of the Second Eunuch, Kafur

- The Tale of King Omar bin al-Nu’uman and His Sons Sharrkan and Zau al-Makan

- Tale of Tàj al-Mulúk and the Princess Dunyà: The Lover and the Loved

- Tale of Azíz and Azízah

- Tale of Tàj al-Mulúk and the Princess Dunyà: The Lover and the Loved

Volume 3

- The Tale of King Omar Bin al-Nu’uman and His Sons Sharrkan and Zau al-Makan (continued)

- Tale of Tàj al-Mulúk and the Princess Dunyà: The Lover and the Loved (continued)

- Continuation of the Tale of Aziz and Azizah

- Tale of the Hashish Eater

- Tale of Hammad the Badawi

- Tale of Tàj al-Mulúk and the Princess Dunyà: The Lover and the Loved (continued)

- The Birds and Beasts and the Carpenter

- The Hermits

- The Water-Fowl and the Tortoise

- The Wolf and the Fox

- Tale of the Falcon and the Partridge

- The Mouse and the Ichneumon

- The Cat and the Crow

- The Fox and the Crow

- The Flea and the Mouse

- The Saker and the Birds

- The Sparrow and the Eagle

- The Hedgehog and the Wood Pigeons

- The Merchant and the Two Sharpers

- The Thief and His Monkey

- The Foolish Weaver

- The Sparrow and the Peacock

- Tale of Ali bin Bakkar and Shams al-Nahar

- Tale of Kamar al-Zaman

Volume 4

- Tale of Kamar al-Zaman (continued)

- Ni’amah bin al-Rabi’a and Naomi His Slave-Girl

- Conclusion of the Tale of Kamar al-Zaman

- Ala al-Din Abu al-Shamat

- Hatim of the Tribe of Tayy

- Tale of Ma’an the Son of Zaidah

- Ma’an the Son of Zaidah and the Badawi

- The City of Labtayt

- The Caliph Hisham and the Arab Youth

- Ibrahim bin al-Mahdi and the Barber-Surgeon

- The City of Many-Columned Iram and Abdullah Son of Abi Kilabah

- Isaac of Mosul

- The Sweep and the Noble Lady

- The Mock Caliph

- Ali the Persian

- Harun al-Rashid and the Slave-Girl and the Imam Abu Yusuf

- Tale of the Lover Who Feigned Himself a Thief

- Ja’afar the Barmecide and the Bean-Seller

- Abu Mohammed hight Lazybones

- Generous Dealing of Yahya bin Khalid The Barmecide with Mansur

- Generous Dealing of Yahya Son of Khalid with a Man Who Forged a Letter in his Name

- Caliph Al-Maamun and the Strange Scholar

- Ali Shar and Zumurrud

- The Loves of Jubayr bin Umayr and the Lady Budur

- The Man of Al-Yaman and His Six Slave-Girls

- Harun al-Rashid and the Damsel and Abu Nowas

- The Man Who Stole the Dish of Gold Wherein The Dog Ate

- The Sharper of Alexandria and the Chief of Police

- Al-Malik al-Nasir and the Three Chiefs of Police

- The Story of the Chief of Police of Cairo

- The Story of the Chief of the Bulak Police

- The Story of the Chief of the Old Cairo Police

- The Thief and the Shroff

- The Chief of the Kus Police and the Sharper

- Ibrahim bin al-Mahdi and the Merchant’s Sister

- The Woman whose Hands were Cut Off for Giving Alms to the Poor

- The Devout Israelite

- Abu Hassan al-Ziyadi and the Khorasan Man

- The Poor Man and His Friend in Need

- The Ruined Man Who Became Rich Again Through a Dream

- Caliph al-Mutawakkil and his Concubine Mahbubah

- Wardan the Butcher; His Adventure With the Lady and the Bear

- The King’s Daughter and the Ape

Volume 5

- The Ebony Horse

- Uns al-Wujud and the Vizier’s Daughter al-Ward Fi’l-Akmam or Rose-In-Hood

- Abu Nowas With the Three Boys and the Caliph Harun al-Rashid

- Abdallah bin Ma’amar With the Man of Bassorah and His Slave Girl

- The Lovers of the Banu Ozrah

- The Wazir of al-Yaman and His Younger Brother

- The Loves of the Boy and Girl at School

- Al-Mutalammis and His Wife Umaymah

- The Caliph Harun al-Rashid and Queen Zubaydah in the Bath

- Harun al-Rashid and the Three Poets

- Mus’ab bin al-Zubayr and Ayishah Daughter of Talhah

- Abu al-Aswad and His Slave-Girl

- Harun al-Rashid and the Two Slave-Girls

- The Caliph Harun al-Rashid and the Three Slave-Girls

- The Miller and His Wife

- The Simpleton and the Sharper

- The Kazi Abu Yusuf With Harun al-Rashid and Queen Zubaydah

- The Caliph al-Hakim and the Merchant

- King Kisra Anushirwan and the Village Damsel

- The Water-Carrier and the Goldsmith’s Wife

- Khusrau and Shirin and the Fisherman

- Yahya bin Khalid the Barmecide and the Poor Man

- Mohammed al-Amin and the Slave-Girl

- The Sons of Yahya bin Khalid and Sa’id bin Salim al-Bahili

- The Woman’s Trick Against Her Husband

- The Devout Woman and the Two Wicked Elders

- Ja’afar the Barmecide and the Old Badawi

- The Caliph Omar bin al-Khattab and the Young Badawi

- The Caliph al-Maamun and the Pyramids of Egypt

- The Thief and the Merchant

- Masrur the Eunuch and Ibn al-Karibi

- The Devotee Prince

- The Unwise Schoolmaster Who Fell in Love by Report

- The Foolish Dominie

- The Illiterate Who Set Up For a Schoolmaster

- The King and the Virtuous Wife

- Abd al-Rahman the Maghribi’s Story of the Rukh

- Adi bin Zayd and the Princess Hind

- Di’ibil al-Khuza’i With the Lady and Muslim bin al-Walid

- Isaac of Mosul and the Merchant

- The Three Unfortunate Lovers

- How Abu Hasan Brake Wind

- The Lovers of the Banu Tayy

- The Mad Lover

- The Prior Who Became a Moslem

- The Loves of Abu Isa and Kurrat al-Ayn

- Al-Amin Son of al-Rashid and His Uncle Ibrahim bin al-Mahdi

- Al-Fath bin Khakan and the Caliph Al-Mutawakkil

- The Man’s Dispute With the Learned Woman Concerning the Relative Excellence of Male and Female

- Abu Suwayd and the Pretty Old Woman

- The Emir ali bin Tahir and the Girl Muunis

- The Woman Who had a Boy and the Other Who had a Man to Lover

- Ali the Cairene and the Haunted House in Baghdad

- The Pilgrim Man and the Old Woman

- Abu al-Husn and His Slave-Girl Tawaddud

- The Angel of Death With the Proud King and the Devout Man

- The Angel of Death and the Rich King

- The Angel of Death and the King of the Children of Israel

- Iskandar Zu al-Karnayn and a Certain Tribe of Poor Folk

- The Righteousness of King Anushirwan

- The Jewish Kazi and His Pious Wife

- The Shipwrecked Woman and Her Child

- The Pious Black Slave

- The Devout Tray-Maker and His Wife

- Al-Hajjaj and the Pious Man

- The Blacksmith Who Could Handle Fire Without Hurt

- The Devotee To Whom Allah Gave a Cloud for Service and the Devout King

- The Moslem Champion and the Christian Damsel

- The Christian King’s Daughter and the Moslem

- The Prophet and the Justice of Providence

- The Ferryman of the Nile and the Hermit

- The Island King and the Pious Israelite

- Abu al-Hasan and Abu Ja’afar the Leper

- The Queen of Serpents

- The Adventures of Bulukiya

- The Story of Janshah

- The Adventures of Bulukiya (resumed)

- The Queen of Serpents (resumed)

Volume 6

- Sindbad the Seaman and Sindbad the Landsman

- The First Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Second Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Third Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Fourth Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Fifth Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Sixth Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The Seventh Voyage of Sindbad the Seaman

- The City of Brass

- The Craft and Malice of Woman, or the Tale of the King, His Son, His Concubine and the Seven Viziers

- The King and His Vizier’s Wife

- The King’s Son and the Merchant’s Wife

- The Page Who Feigned to Know the Speech of Birds

- The Lady and Her Five Suitors

- The Three Wishes, or the Man Who Longed to see the Night of Power

- The Stolen Necklace

- The Two Pigeons

- Prince Behram and the Princess Al-Datma

- The House With the Belvedere

- The King’s Son and the Ifrit’s Mistress

- The Sandal-Wood Merchant and the Sharpers

- The Debauchee and the Three-Year-Old Child

- The Stolen Purse

- The Fox and the Folk

- Judar and His Brethren

- The History of Gharib and His Brother Ajib

Volume 7

- The History of Gharib and His Brother Ajib (continued)

- Otbah and Rayya

- Hind Daughter of Al-Nu’man, and Al-Hajjaj

- Khuzaymah Bin Bishr and Ikrimah Al-Fayyaz

- Yunus the Scribe and the Caliph Walid Bin Sahl

- Harun al-Rashid and the Arab Girl

- Al-Asma’i and the Three Girls of Bassorah

- Ibrahim of Mosul and the Devil

- The Lovers of the Banu Uzrah

- The Badawi and His Wife

- The Lovers of Bassorah

- Ishak of Mosul and His Mistress and the Devil

- The Lovers of Al-Medinah

- Al-Malik Al-Nasir and His Wazir

- The Rogueries of Dalilah the Crafty and Her Daughter Zaynab the Coney-Catcher

- The Adventures of Mercury Ali of Cairo

- Ardashir and Hayat al-Nufus

- Julnar the Sea-Born and Her Son King Badr Basim of Persia

- King Mohammed Bin Sabaik and the Merchant Hasan

- Story of Prince Sayf al-Muluk and the Princess Badi’a al-Jamal

Volume 8

- King Mohammed Bin Sabaik and the Merchant Hasan (continued)

- Story of Prince Sayf al-Muluk and the Princess Badi’a al-Jamal (continued)

- Hassan of Bassorah

- Khalifah The Fisherman Of Baghdad

- Masrur and Zayn al-Mawasif

- Ali Nur al-Din and Miriam the Girdle-Girl

Volume 9

- Ali Nur al-Din and Miriam the Girdle-Girl (continued)

- The Man of Upper Egypt and His Frankish Wife

- The Ruined Man of Baghdad and his Slave-Girl

- King Jali’ad of Hind and His Wazir Shimas

- The History of King Wird Khan, son of King Jali’ad with His Women and Viziers

- The Mouse and the Cat

- The Fakir and His Jar of Butter

- The Fishes and the Crab

- The Crow and the Serpent

- The Wild Ass and the Jackal

- The Unjust King and the Pilgrim Prince

- The Crows and the Hawk

- The Serpent-Charmer and His Wife

- The Spider and the Wind

- The Two Kings

- The Blind Man and the Cripple

- The Foolish Fisherman

- The Boy and the Thieves

- The Man and his Wife

- The Merchant and the Robbers

- The Jackals and the Wolf

- The Shepherd and the Rogue

- The Francolin and the Tortoises

- The History of King Wird Khan (resumed)

- Abu Kir the Dyer and Abu Sir the Barber

- Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman

- Harun Al-Rashid and Abu Hasan, The Merchant of Oman

- Ibrahim and Jamilah

- Abu Al-Hasan of Khorasan

- Kamar Al-Zaman and the Jeweller’s Wife

- Abdullah bin Fazil and His Brothers

Volume 10

- Ma’aruf the Cobbler and His Wife Fatimah

- Conclusion of Shahrazad and Shahryar

Supplemental Nights, Volume 1

- The Sleeper and the Waker

- The Caliph Omar Bin Abd al-Aziz and the Poets

- Al-Hajjaj and the Three Young Men

- Harun al-Rashid and the Woman of the Barmecides

- The Ten Wazirs; or the History of King Azadbakht and His Son

- Story of the Merchant Who Lost His Luck

- Tale of the Merchant and His Sons

- Story of Abu Sabir

- Story of Prince Bihzad

- Story of King Dadbin and His Wazirs

- Story of King Bakhtzaman

- Story of King Bihkard

- Story of Aylan Shah and Abu Tammam

- Story of King Ibrahim and his Son

- Story of King Sulayman Shah and his Niece

- Story of the Prisoner and how Allah gave him Relief

- Ja’afar Bin Yahya and Abd al-Malik bin Salih the Abbaside

- Al-Rashid and the Barmecides

- Ibn al-Sammak and al-Rashid

- Al-Maamum and Zubaydah

- Al-Nu’uman and the Arab of the Banu Tay

- Firuz and His Wife

- King Shah Bakht and his Wazir Al-Rahwan

- Tale of the Man of Khorasan, His Son and His Tutor

- Tale of the Singer and the Druggist

- Tale of the King Who Kenned the Quintessence of Things

- Tale of the Richard Who Married His Beautiful Daughter to the Poor Old Man

- Tale of the Sage and His Three Sons

- Tale of the Prince who Fell in Love With the Picture

- Tale of the Fuller and His Wife and the Trooper

- Tale of the Merchant, The Crone, and the King

- Tale of the Simpleton Husband

- Tale of the Unjust King and the Tither

- Story of David and Solomon

- Tale of the Robber and the Woman

- Tale of the Three Men and Our Lord Isa

- Tale of the Dethroned Ruler Whose Reign and Wealth Were Restored to Him

- Tale of the Man Whose Caution Slew Him

- Tale of the Man Who Was Lavish of His House and His Provision to One Whom He Knew Not

- Tale of the Melancholist and the Sharper

- Tale of Khalbas and his Wife and the Learned Man

- Tale of the Devotee Accused of Lewdness

- Tale of the Hireling and the Girl

- Tale of the Weaver Who Became a Leach by Order of His Wife

- Tale of the Two Sharpers Who Each Cozened His Compeer

- Tale of the Sharpers With the Shroff and the Ass

- Tale of the Chear and the Merchants

- Story of the Falcon and the Locust

- Tale of the King and His Chamberlain’s Wife

- Story of the Crone and the Draper’s Wife

- Tale of the Ugly Man and His Beautiful Wife

- Tale of the King Who Lost Kingdom and Wife and Wealth and Allah Restored Them to Him

- Tale of Salim the Youth of Khorasan and Salma, His Sister

- Tale of the King of Hind and His Wazir

Supplemental Nights, Volume 2

- Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Bibars al-Bundukdari and the Sixteen Captains of Police

- Tale of Harun al-Rashid and Abdullah bin Nafi’

- Women’s Wiles

- Nur al-Din Ali of Damascus and the Damsel Sitt al-Milah

- Tale of King Ins bin Kays and His Daughter with the Son of King Al-‘Abbas

Supplemental Nights, Volume 3 (Galland’s “Orphan Tales”)

- The Tale of Zayn al-Asnam

- Alāʼ ad-Dīn and The Wonderful Lamp

- Khudadad and His Brothers

- The Caliph’s Night Adventure

- The Story of the Blind Man, Baba Abdullah

- History of Sidi Nu’uman

- History of Khwajah Hasan al-Habbal

- Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

- Ali Khwajah and the Merchant of Baghdad

- Prince Ahmad and the Fairy Peri-Banu

- The Two Sisters Who Envied Their Cadette

Supplemental Nights, Volume 4

- The Tale of Zeyn Al-Asnam (a.k.a. Prince Zayn al-Asnam and the King of the Jinn)

- Alaeddin; or, The Wonderful Lamp

- The Tale of Kamar al-Zaman and the Jeweller’s Wife

- Shorter anecdotes: The Caliph and the Three Kalandars (variant), The Fisherman of Cairo, etc.

Supplemental Nights, Volume 5

- The Tale of the Two Sisters Who Envied Their Cadette

- The Tale of the Princess of Deryabar

- The Enchanted Horse (alternate version)

- The City of Brass (variant)

- Plus court anecdotes, rogues’ tales, erotic episodes

Supplemental Nights, Volume 6:

- The Story of the Sleeper and the Waker.

- The King’s Son and the Ifrit’s Mistress (variant of Seven Viziers cycle)

- The Adventures of Mahmoud the Persian Merchant

- The Tale of the Moor’s Legacy

- Finishes with late Egyptian popular tales, moral anecdotes, and closes the cycle

A Critical Guide to Modern English Collections

For the modern reader, navigating the many available English translations of The Thousand and One Nights can be a daunting task. The choice of translation is not merely a matter of style; it determines which version of the Nights one reads, the older, shorter Syrian recension or the later, encyclopedic Egyptian recension. The following analysis details the most significant English editions, assessing their source texts, completeness, and scholarly value.

The Scholarly Core: The Mahdi-Haddawy Translation (The Syrian Recension)

This two-volume set represents the pinnacle of modern scholarship on the earliest recoverable form of the Nights. It is not a single, unified publication but a pairing of two complementary books.

- Source Text: The translation is based on the 1984 critical Arabic edition prepared by Muhsin Mahdi. Mahdi’s edition is a painstaking reconstruction of the text as found in the 14th-century Galland Manuscript, the oldest extensive witness to the Syrian recension.

- Content and Publications:

- The Arabian Nights (translated by Husain Haddawy, 1990): This volume contains a direct and faithful translation of Mahdi’s edition, presenting the stories from the Galland Manuscript up to the point where it breaks off on Night 282. It is prized for its clear, elegant prose that captures the literary quality of the original Arabic.

- The Arabian Nights II: Sindbad and Other Popular Stories (translated by Husain Haddawy, 1995): Recognizing that readers would miss the most famous tales, Haddawy produced this companion volume. It contains fresh translations of the major “orphan tales”, “Sindbad the Sailor,” “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” and “Aladdin and the Magic Lamp”, along with other popular stories not found in the Galland Manuscript.

- Assessment: The Mahdi-Haddawy set is the essential starting point for any serious reader. It provides an unparalleled experience of the Nights in its most historically authentic form. By presenting the orphan tales in a separate volume, it respects their distinct textual history while still making them available. For understanding the literary core of the tradition, this translation is indispensable.

The Modern Standard: The Lyons Translation (The Egyptian Recension)

For readers seeking a complete, modern, and scholarly translation of the entire 1001-night tradition, the three-volume Penguin Classics edition is the definitive choice.

- Source Text: This translation by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons is based on the Calcutta II (Macnaghten) edition of 1839-42, the most complete and influential printed Arabic text of the Egyptian recension.

- Content: Published in 2008, this is the first complete, direct English translation of the Calcutta II text since Burton’s in the 1880s. Across its three substantial volumes, it presents the full, unexpurgated collection of tales from the Egyptian tradition. It also includes new translations of the Galland/Diab “orphan tales,” such as “Aladdin” and “Ali Baba,” for which no pre-18th-century Arabic source exists, thereby offering a truly comprehensive collection.

- Assessment: The Lyons translation has superseded Burton’s as the modern standard for a “complete” Nights. Its prose is contemporary, clear, and unexpurgated without being sensationalistic. Accompanied by an introduction and notes by the scholar Robert Irwin, it is both accessible to the general reader and valuable to the student. For anyone who wants the full, sprawling, encyclopedic experience of the Nights as it has been known for the last two centuries, this is the most authoritative and readable version available.

The Unexpurgated Victorian Classic: Sir Richard F. Burton’s Translation

Sir Richard F. Burton’s translation is less a text and more a cultural monument, a work as famous for its translator’s personality as for the stories themselves.

- Source Text: Burton’s translation is primarily based on the Calcutta II edition, though he consulted numerous other sources and was heavily indebted to the preceding translation by John Payne.

- Content: Published privately for subscribers between 1885 and 1888, The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night consists of ten primary volumes and six (sometimes reprinted as seven) supplemental volumes. It was, until the Lyons edition, the only complete and unexpurgated English translation. It is legendary for its voluminous and deeply idiosyncratic footnotes, terminal essay, and appendices, which contain Burton’s wide-ranging and often explicit observations on Middle Eastern culture, social mores, and sexual practices.

- Assessment: Burton’s Nights is a landmark of Victorian scholarship and Orientalism. However, for the modern reader, it presents significant challenges. Burton deliberately employed a highly artificial and archaic prose style, a “mock-Gothic” blend of Chaucerian and Jacobean English, filled with obscure words like ‘chevisance’ and ‘wittol’. This makes the text dense and often difficult to read. While historically significant and admired by figures like Jorge Luis Borges for its ambition, it is now primarily of interest to specialists, collectors, and those studying the history of translation and Orientalism.

Other Influential (but Incomplete) Editions

- Edward William Lane (1839–41): Based on the Bulaq printed edition, Lane’s translation was hugely popular in the 19th century. Its primary value today lies in its extensive and accurate notes on the customs and manners of 19th-century Cairenes. However, the translation itself is severely flawed by modern standards. Lane was deeply censorious, heavily bowdlerizing the text to make it “decent” for a Victorian household, omitting any tales or passages he deemed immoral or irreligious. It is therefore an incomplete and sanitized version of the work.

- John Payne (1882–84): Payne’s The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night was the first complete and unexpurgated English translation, predating Burton’s by a few years. Printed privately in a small run, it is a scholarly and accurate work, but it was quickly overshadowed by Burton’s more flamboyant and aggressively marketed version. It remains a work of specialist interest, crucial to the history of the English Nights but largely superseded for the general reader.

Recommendation: Assembling a Complete Library of The Thousand and One Nights

The preceding analysis demonstrates that no single volume can claim to be the sole “authentic” or “complete” version of The Thousand and One Nights. The collection exists in distinct forms, each with its own historical and literary integrity. Therefore, the ideal approach for acquiring a comprehensive library of the tales depends on the reader’s specific goals: scholarly understanding, comprehensive coverage, or historical appreciation.

The Foundational Collection: The Earliest Core and the Essential “Orphans”

For the reader who prioritizes scholarly authenticity and wishes to experience the Nights in its oldest recoverable form, while also reading the famous tales whose separate origins are now understood, the following two-volume set is the premier recommendation:

- Haddawy, Husain (translator). The Arabian Nights. W.W. Norton, 1990. This volume contains the pure text of the 14th-century Syrian recension, based on Muhsin Mahdi’s critical edition. It is the literary and historical core of the tradition.

- Haddawy, Husain (translator). The Arabian Nights II: Sindbad and Other Popular Stories. W.W. Norton, 1995. This essential companion provides masterful translations of the “orphan tales” (Sindbad, Aladdin, Ali Baba) and other stories that have become culturally inseparable from the Nights, while respecting their distinct textual history.

This pairing offers the most intellectually honest and historically nuanced collection. It allows the reader to appreciate the ancient core and the famous later additions as related but distinct literary entities, providing the clearest possible view of the work’s evolution.

The Definitive “Complete” Collection: The Modern Scholarly Standard

For the reader who seeks the most comprehensive collection of tales traditionally associated with the Nights in a single, modern, accessible, and scholarly translation, the definitive recommendation is the three-volume set translated by Malcolm C. Lyons and Ursula Lyons:

- Lyons, Malcolm C. and Ursula Lyons (translators). The Arabian Nights: Tales of 1,001 Nights, Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Penguin Classics, 2008.

This set is the modern gold standard for a “complete” Nights. It provides an unexpurgated and highly readable translation of the entire, expansive Calcutta II edition, the most complete printed Arabic recension. It also seamlessly integrates the crucial “orphan tales,” presenting the entire tradition as it has been known for the past two centuries in one authoritative and beautifully produced collection. This edition effectively replaces the Burton translation as the go-to version for both completeness and readability.

The Historical Artifact: The Collector’s and Specialist’s Choice

For the historical enthusiast, the student of 19th-century Orientalism, or the dedicated collector, the monumental work of Sir Richard F. Burton remains a compelling, if challenging, acquisition:

- Burton, Sir Richard F. (translator). The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (10 volumes) and The Supplemental Nights (6-7 volumes). 1885–1888.

While its deliberately archaic prose makes it unsuitable as a primary reading text for most, Burton’s edition is an unparalleled document of its era. Its extensive and idiosyncratic notes offer a unique, if controversial, window into Victorian ethnography, comparative mythology, and Orientalist thought. It is a work to be studied as a historical artifact in its own right and should be acquired in addition to, not as a substitute for, the modern translations by Haddawy or Lyons.

Leave a comment